I want to collapse the sky

into braille

then run your fingers over it

because we are blind

under a vast canopy of unspeakable promise.

I want to collapse the sky

into braille

then run your fingers over it

because we are blind

under a vast canopy of unspeakable promise.

Exegesis is the interpretation of text, or the drawing out meaning based on the contexts of its creation.

Eisegesis is the insertion of one’s ideas into text.

1. Why an apple in the guddenovaiden?

2. Truth is we made it an apple.

3. Coulda beena fig or a pomegranet, a pear ora peach.

4. A fruit by any other name would be as bitter.

5. Thus, I make it an orange.

6. I have the power to name, remember?

6.1.1 (Bestowed on me by the alleged originator of said tree, previously mentioned.)

7. An orange is segmented, shareable, and leans well into metaphor.

7.1 It is an adjective, a noun and a verb. A trifecta, a trinity.

8. If you’re going for damnation, orange contrasts well with the purple that rises with a bruise.

9. But, before you go, a word on The Fall.

9.1 The reports of my fall have been highly exaggerated.

9.2 One understands the need for drama when dealing with a restless populace with tendencies to deviation from the favoured narrative.

10. What to do?

11. Interrogate the narrative.

11.1 Who would favour the notion of a fall? And what is a fall exactly?

11.2 It was a Fall from Grace they said.

11.3 A separation from Source, they said.

11.4 Spiritual Death they said, to frame the route to salvation.

11.5 This route they said was given to them for safekeeping.

11.6 None went to the Father except by them, they said.

11.7 Two millenia of crowd control.

11.8 Nothing nurtures obsequiousness like the promise of damnation.

11.9 Them that think they’re broken, stay broken.

12. They breed brokeness.

12.1 They look for blame and find me.

13. But,

13.1 we were always wonderfully unbroken.

13.2 And remain so.

14. Fly my unfallen progeny.

I hope you are at least happy together in quieter moments, away from the camera. I hope there are moments where love is demonstrated in unrehearsed gestures. Like fingers touching intentionally that lead them to pause and hold and linger gently in the hold of each other.

Some days, you’ll feel the drag of 5515 kg/m³ travelling at 107 000 km/h through the wind in your hair.

And, thumb swipes present the world, between cats and close-ups of grated play dough, that hell is unleashed on planet earth.

Six feeds of disaster with thumbnails of human wreckage hashtag worldgonemad will have us forget to find the blue sky over our heads.

Here is where the world is. This is all of it, as long as I live. I can take care of this.

and yes, after Plato found his way through the fence and demolished the vegetable garden, I was angry. Because I had warned you. Because you dismissed my concerns as “neurotic.” Now the cold weather is here. You will need to take risks that might have been avoided.

More precisely, you will need to ask others to take risks on your behalf. I was wrong to take my frustration out on you. I’m sorry. I’m sorry about Plato. I loved him, too. Perhaps his name was bad luck? I never cared for the original Plato. But I loved our Plato. And I am weary of digging holes for those I love. We are either digging holes or filling them … we’re never whole.

Understanding is retrospective and usually too late to be of any use. So, no regrets. We live, we love, and then, as Oscar Wilde told us, we kill the things we love. I admit that in my distress (after the event), I blamed you. I cursed and cried that he would be alive if River had been more vigilant. That was unfair. Blame is a coward’s balm. So, now I must confront my rage.

How does one confront something so intimate and, at the same time, so foreign? When I was a child, my first pet was a cockatiel. I was devoted to him. I tamed him, taught him to whistle the Colonel Bogey. I loved him. One day, while he sat on my shoulder, he nuzzled into my neck, as was his habit, and I leaned in slightly to acknowledge him. I don’t know why, but he bit into my ear and would not let go. I bled profusely. I recall the shock and anger I felt. How could he hurt the one who loved him most?

I closed my hand around him and pulled until his locked beak loosed its grip on my ear, and he then dug into my thumb. I nearly crushed him to death. A wave of rage ran through me and terrified me. I think the intensity of my feelings shocked me. I slipped him back into his cage. I did not know myself anymore.

It is not enough to survive, River.

But, despite the tensions we were soldiers first and Kreet was the land that bound us, both the unwilling and the blind. The hour before sunrise is the coldest. The wind picks up and the chill settles on the bones. You can run for the whole hour and not feel warmed up inside. But any time away from the camp is a relief. Especially now with the prisoners there. The enemy prisoners. We prefer the 1am duty. The guardhouse is noisy until 11pm anyway and the chance of being hauled away for some dirty job is high. At one in the morning the world feels like a peaceful place. The lights in town shimmer, the lights of the main road hang beneath the horizon like pots of fire. Once a barn owl swooped over our heads as we sat in the grass smoking a cigarette, cupping our hands over it carefully to avoid detection and putting our heads between our knees to suck in the smoke and hide the soft glow. We felt it before we heard it. It sounded like something big breathing out over us. We felt a quick rush of cool air on our necks and then heard a swoosh. Between feeling the owl and hearing it we had rolled away and were aiming at the blackness behind us. After a kilometre we started laughing uncontrollably and sat down again and smoked a cigarette but coughed a lot through laughter. That was one of the happiest moments from that time. It bound us and allowed us to remain friends after the difficulties later. That we could laugh together gave each of us permission to forgive one another later.

There was this evening in the beer garden. Blokes getting drunk and forgetting stuff they had seen or done and finding absolution in the wordless confessional of alcohol.

We have to fight to hold onto our land, Kreet is ours someone said. Maybe the beer had given me courage? Maybe the guilt of silent collusion got the better of me?

Is it really our land? I said. The Company officer, the one who had forced us to leopard crawl over slate and laughed as we had bled, was there. Like dogs we were eager for his approval. We imagined he had become a friend.

You’re crossing a line he said.

A veil of distrust descended over us. Things continued as normal after that but dialogue strained as if emerging every time tired from a long journey through an internal labyrinth where pre verbalised thoughts were considered according to possible interpretations and consequences. Everyone became cautious, having to hold the thread of the original thought while surveying the various landscapes that began to form and take shape as a result of the words spoken. Conversation collapsed under the pressure and became chatter skimming along the surface of things: the weather, physical ailments, safe complaints about people mutually agreed upon to be fools and the camp dog, Asterion. It was always safe and comforting to share stories about Asterion’s antics as if talking about him bridged the abyss deepening beteeen us.

That was all a long time ago and Kreet is reclaimed now. Those who were once prisoners now lead and those who used to lead have been imprisoned. I wonder now if we were soldiers protecting the land or minotaurs prowling the imagined idea of a country in the subterranean labyrinth of some nameless terrain in wait for a name change? The friend with the owl now farms the land and I exiled myself from it.

The new country has a name but I have become weary of names for land. There are leaders here also, I’m not sure yet whether they lead soldiers or minotaurs. I was a minotaur once. Now I look for Asterion instead. There is always an Asterion. I only saw an owl once. There are prisoners here, they are everywhere.

The thing about nature is this, it wants to kill you. It’s nothing personal, simply the default position by which it operates. The law of entropy governs the molecules that make up the world and they want to get you unto dust as soon as possible.

The scientific term for the gradual degradation of life forms is entropy. Simply stated, things move from a state of order to one of disorder. Think of ‘order‘ here as the way we manipulate molecules to make stuff. What we think of as order is our construction of the world. Disorder is the state of the world before we intervened. We heat and smelt iron molecules to make steel. Over time the constructed molecules break down, rust occurs. Whatever humans make from matter eventually degrades- that’s entropy. The molecules aren’t being hostile or uncooperative, it takes effort to maintain an imposed form. It takes less energy to let go than to hold on. Modern existence is a series of artificial constructions. Order and disorder are human terms which reflect our prejudices, not the state of the world. Maintaining the illusion of order takes time and energy.

Perhaps it’s just that the simplicity of a tent or a caravan loosens momentarily the noose of financial bondage around our necks. The Big Outside nourishes our dreams of reinvention and freedom from various interminable forms of control. We do not purchase a house; we trade a lifetime of labour for the vague dream of financial freedom. All narratives end.

Getting back to nature is not a return to some ideal state. It is, at best, an escape from the soulless tedium of modernity and, at worst, delusion on a grand scale.

From the safety of suburbia and city apartments, nature still holds tremendous appeal. It represents escape from our hamster wheel routines, mind-numbing commutes and over-peopled places.

But towns and cities are underrated and have had an unfair press ever since Charles Dickens revealed their underbelly in the late 19th century.

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution rural life became romanticised. A return to nature became the rallying cry of poets like Wordsworth and philosophers like Jean Jacques Rousseau. With nature subdued to landscaped gardens we soon forgot that we had to fight nature to survive. It took thousands of years of struggle to get a roof over our heads, and once safely inside we gazed through our windows at the garden with nostalgia.

We have romanticised nature. Here in Australia people often wander into the Outback and never return. We’ve forgotten that nature is nice, from a safe distance.

We cannot escape our lives. The issues that assail us are not location specific. They will find us whether we are living in suburbia, a city apartment, a forest or on top of a mountain. Geography does not alter the state of the soul, but keep a soul in one place long enough and it’s bound to chaffe.

Maybe geography does alter the state of the soul after all?

Aging is like entering a Hall of Mirrors. The body undergoes rapid distortion. The present melts into comic and hellish reflections. You laugh, but you want to cry. Reality is stripped of its rigid adherence to a single form. You emerge as a multitudinous distortion. There is a reluctant acknowledgement of the fragmented nature of all things. Maybe this is some kind of enlightenment? A surrendering of sorts? A release of the need for a fixed position in the experience of existence.

Holding onto anything is exhausting and sooner or later one finds that holding on has become a habit. Sometimes we refer to this as endurance.

Youth is the vigour of life in full bloom. A sweet and beautiful reminder of all that is good. A boundless time in which eternity feels real because the body moves with such ease through the world that anything is possible. We are, then, an expression of the elegant logic of being. So we move on, around the sun, again and again … and find ourselves one afternoon, suddenly tired. The shadow we cast does not stretch as far as it used to. Gravity feels stronger than eternity.

Life is a mighty force contained in our physical form. Briefly, force and form find equilibrium. We run, we are limitless, we fly. Gradually, the fragility of our form begins to show. Life, once all-giving, seems to slowly recede, taking parts of us with it: teeth, joints, people, places, dreams. One atom at a time, over time and bit by bit we experience subtraction. We are compelled to minimalism and to accomodate this shift we slowly retreat from the world until we are away from the noise and the bustle, in the high tower of Self. We gather memories like feathers hoping to feel again the delight of flight.

We gather them up and stitch them together to make wings we hope will allow us fly. Like Daedalus and Icarus we survey the vast landscape upon which past dramas were played out.

And of course we never fly. But, it is essential that we never lose hope of taking flight. Hope is the air that fills the sky, but also permeates the earth. Air.

You remember the road, the drive, the peripheral blur of veldt. You know why cosmos smell like Marlboro Gold. You saw the sunflowers at first light through broken ribbons of mist. Shrikes hovered over a dead mouse on the road and you marvelled at how much detail the eye takes in whilst moving at that speed. Maybe looking slows down time? You remember the road.

You recall the cold air sweeping through the cabin. At the tree-lined hilltop bend that holds years of your regret, you stop. This is the last time, you must. It is less than you expected. Turns out, it’s just the side of the road. Cars pass. The air vibrates. You carry on.

Passing stand-out trees you’ve seen grow from saplings to bold silhouettes. A farmhouse whose colourful geometric patterns have faded, the mud walls crumbled. Fifteen year old giggles rolling from your daughters trying to say Ndebele, hover here still. Who will ever hear them again?

It’s an abrasive road. Tarmac is rough. Pain on leaving, pain on arriving. Pain on pain. Gethsemanal pain even, once on the side of the road. But also that walk through sunflower fields and thoughts of Vincent, of … and forever after the understanding of his painting of them.

Majuba. The mountain pass with awful imaginings and battlefields and arriving broken. Is my ghost already here? Is this why back in Perth my voice ridicules me? I, he, falls into the safety of second person.

Detached. Stitching memories into memoir. Chucking an unspoken life out the window and getting the hell out while there’s still something to salvage. Leaving a father under a tree on Matakenyane and a mother in a box on a brother’s bedside table.

I gotta igoodea he said under the Frangipani tree that summer and I sat in wonder of him. I still do.

We trawled the soft layers of perfumed petals loosened by time and rain and wind and gathered up falling handfulls of Frangipani. We let them fall soft, yellow-streaked parasols, into the birdbath. What we called the birdbath was actually a large stone that had been hollowed out by the manual crushing of maze over many years in the homes which were scattered throughout the valley. At the end of our childhood we learned that people were crushed too.

There were these warm rains without lightning when we could sit and watch the slate paving change colour and save ants caught in onyx creases from drowning. We called everyone to see but only Sophie came and burst into a song of praise, ai ai yai, sshhoo sschhoo, halala … which startled us both to look again at our handiwork in case we’d missed something. She made us feel like heroes, a good thing to be when you are five and not yet broken.

Then my brother of the igoodea gathered cracked litchi shells to make pyramids on the round concrete steps granpa Jack had made at the garage end of the garden by the avo tree. The rough shells dripped between our toes still purple from sliding the purple river of Jakaranda blooms the rain pushed down the gutters from Lone Tree Hill.

Barberton made brothers of us. Gave us a glimpse of our wholeness before we broke. And now we remember the fractured ones who loved us when they were still gods: Granny Hazel’s tenderness, Granpa Jack’s booming laughter and the smell of paint, Old Granny turning soft and translucent like an exhaled breath of Lavender.

It takes 50 years to unwrap childhood. As long for old questions to be answered. Who taught you to be so brave? I once asked. A memory answered me. You and Aunt Ivy, hand in hand, walking up the road to the shop. She was regal and stern from her army Captain days. You were in drag: high heels, evening gown, string of pearls with ostrich feathers on your five year old head. What a gift she gave you that day!

With you we we’re always on the verge of a very important idea. Brother, you were quicker to see the wonder of the world at our feet. While I imagined things to be done, you would begin walking, and I would follow. We were brave enough together to go anywhere. And we did. You made the world feel like a good place to be. You do that still. I love you for that.

Fellow vassal of need, honest companion,

we residue collectors, exiled together,

in this garden of earthly delights we incense air,

light-bearers of extinguished hope and

heirs to the throne of desolation

Vessel for the ash of my leisure

Little reminder of the end of pleasure

You hold my future,

Asher to ashes

It was fun while it lasted.

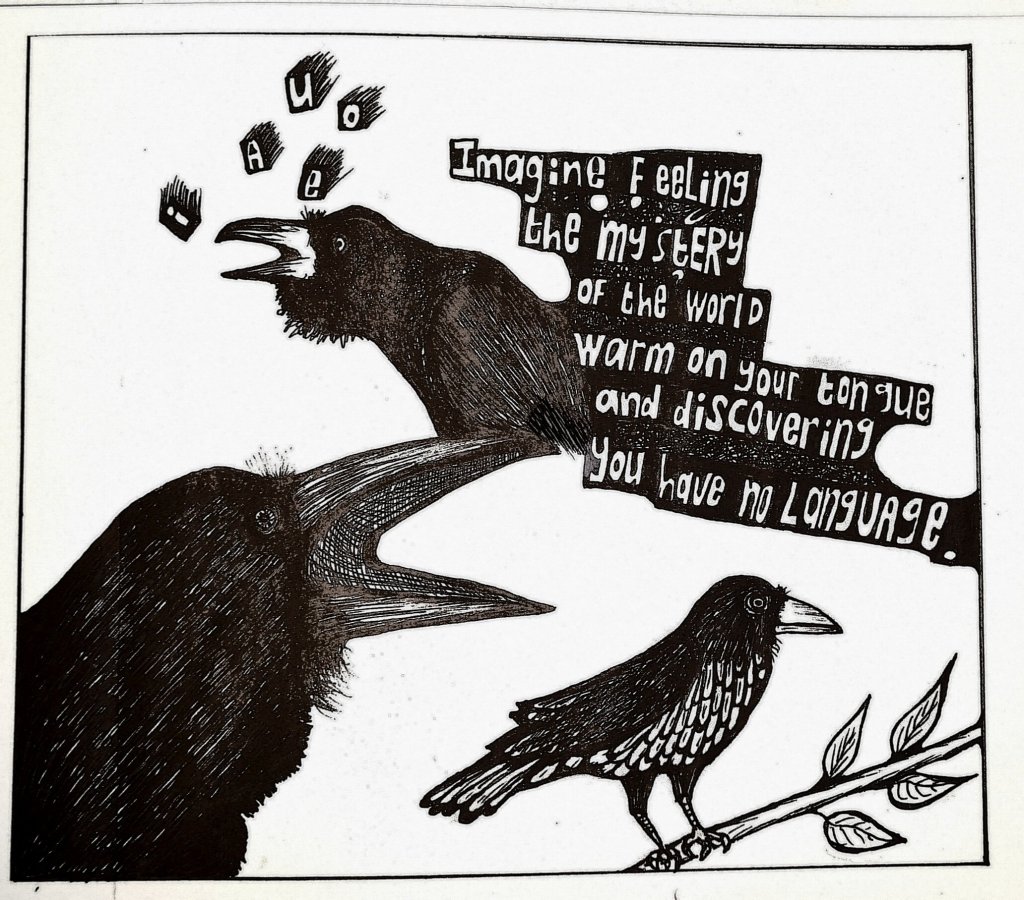

Way back, beyond the reach of living memory, things were different in this world. It’s hard to believe or even imagine how they could be, but they were. The present, after all, is not a solid thing. It is like an invisible curtain we are constantly walking through. We seem to be always peering through it, into a room we never quite enter. So we grasp onto the notion of permanence despite a deep knowingness that nothing endures. This is why we love stories. Stories soften the blows of uncertainty and remind us that we will be alright in the end. Stories cut through the illusions that might otherwise bind us. Take for instance the story of The Raven.

Those noisy black birds that seem to taunt you and strut around like they’re untouchable, they have their story. Legend has it that ravens were once tasked to protect the wisdom of the world. For centuries they fulfilled their duty as the gatekeepers of this wisdom with courage and great nobility of spirit.

Then, one day a dispute emerged between the ravens and the humans. Humans, like ravens, were quick learners, equally intelligent but more arrogant than their counterparts. They challenged the ravens to step down from their assigned role, believing that they were better suited to protect the wisdom of the world. Rivalry between humans and ravens escalated quickly. There had been harsh words before, and words are only words, but they soon have way to violence. The first act of cruelty was quickly avenged and there’s no stopping anyone who feels justified for their brutality. The kingdom came to the brink of civil war. Faced with the potential destruction of the kingdom, the emperor summoned the humans and the ravens to attend an important meeting. Each side arrived convinced that they were right and that the emperor would rule in their favour. The emperor passed a decree which is still in force today. He proclaimed that henceforth all humans would lose their memory of the wisdom of the world or that it even existed, and that the ravens would forget their language except for the vowel sounds: a, e, i, o and u. The key to lifting the curse for both the ravens and humans lay in the form of a specific arrangement of vowel sounds. This curse would be lifted on the day that the humans heard and understood the coded message uttered by the ravens. Since then, sadly, humans have forgotten to listen while many ravens have given up trying to be heard. However, some days, if you are attentive, you will hear through the raven’s caws those letters: a, e, i, o and u. Sometimes you will notice how the ravens appear to be trying to get our attention.

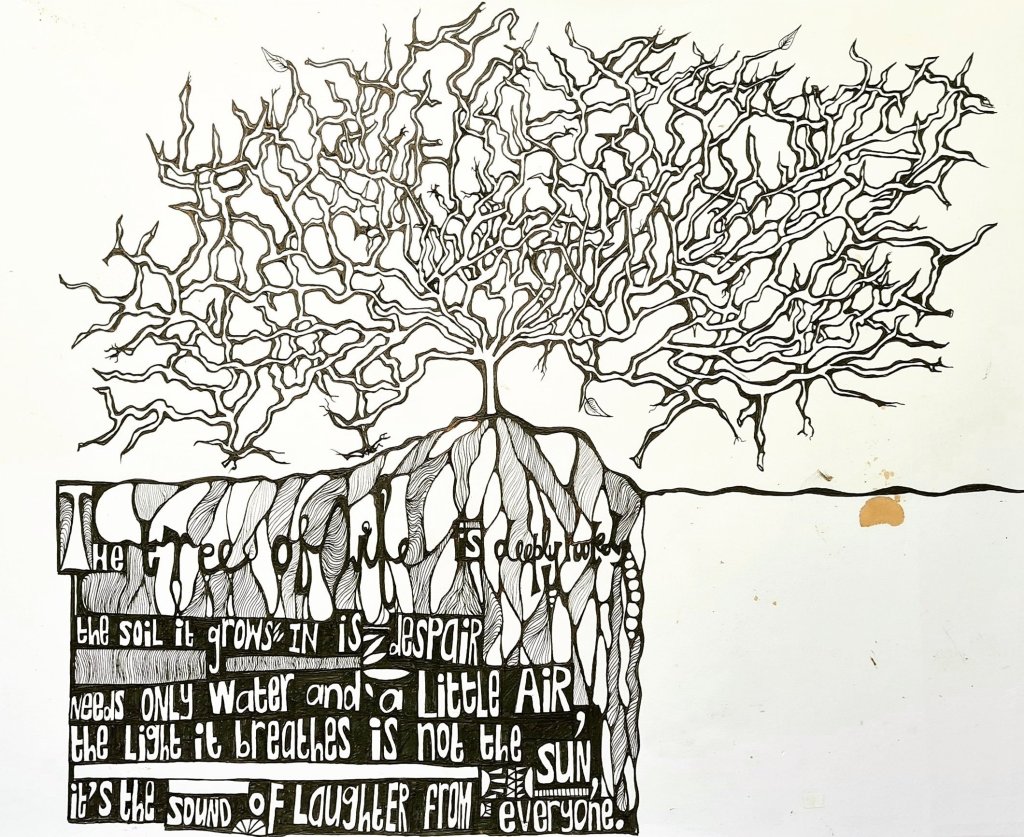

The tree of life is deeply rooted,

the soil it grows in is despair,

needs only water and a little air,

the light it breathes is not the sun,

it’s the sound of laughter

from everyone.